|

|

|

| Saint? | or | Sinner? |

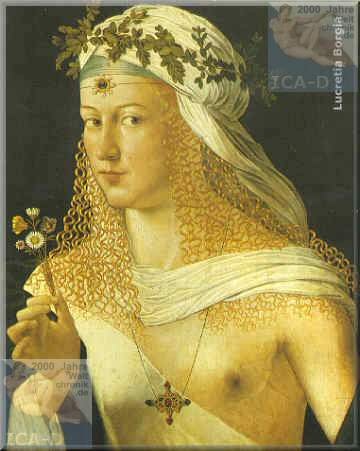

Lucrezia (Lucretia) Borgia: 1480 – 1519Political Pawn or Machiavellian Villain?

Myths & Accusations

Instead of harping on about the alleged incest with her brother Cesare, or the enemies poisoned with powder from a ring on her finger, or the Vatican plotting on behalf of her father, Pope Alexander VI, some claim Lucrezia Borgia was a pious lover of the arts partly responsible for the cultural blossoming of Italy which banished the dark ages. The Italian Renaissance

The years of the greatest influence of the Borgias (1435 - 1520) correspond to one of the most important periods in European history. It is the age of the Renaissance, the beginning of the Age of Exploration, and the age of some of the great rulers, artists, and writers who have influenced our Modern Age. First Crime Family

Unlike the mad Caligula, who killed in insane pleasure, or Nero and his predecessors, who killed for political gain, the Borgias killed not only for pleasure and political gain, but for personal wealth as well. They were, indeed, the first crime family. They were not bound together by blood ritual, but by genes. The Borgias were not exceptional in their lust for riches and land, however. They were simply more ruthless in how they went about it. Alexander VI (1431 - 1503, Pope 1492 - 1503)

Born Rodrigo Borgia near Valencia, Spain, Alexander is the most notorious pope in all of history. He conducted a pontificate of nepotism, greed, ruthlessness, murder, and, as authoritarian McBrien described it, "unbridled sensuality." While a cardinal, he took as his mistress Vannozza de Catanei who bore him four children, including Cesare (born 1475) and Lucrezia (born 1480). He became the leading figure in the saga of the Borgia family, both as a perpetuator of evil and a facilitator of the activities of these two most famous of his children. Like Innocent VIII, Alexander concentrated his efforts on the acquisition of gold, the pursuit of women, and the interests of his family. Much of his strategy entailed the marrying off of his daughter, Lucrezia, a total of three times to progressively wealthier and more influential families. Lucrezia’s first marriage was to Giovanni Sforza, but it was annulled. She was then married to Alfonso of Aragon, who was murdered. Her third and last marriage was to the Duke of Ferrara. Cesare (1476 - 1507)

Cesare's lasting legacy is that he served as the model for Niccolo Machiavelli's The Prince, the leader who promotes himself solely through the strength of his own will. The adjective "Machiavellian,” therefore, describes Cesare Borgia, the embodiment of the practical, ruthless, amoral code of power known as realpolitik. Lucrezia’s Life & MarriagesFirst Marriage: Giovanni Sforza

After spending two years as the Countess of Pesaro, located in the region where the Pope had sent his son-in-law on a military expedition, Lucrezia returned to Rome with her husband. She served as her father's hostess at diplomatic receptions. Soon, Giovanni Sforza's presence in the papal court meant nothing, since the Borgias no longer needed the Sforzas. New political alliances made the link to the Sforza family no longer of significance to the pope. Lucrezia, informed by her brother Cesare that Giovanni was to be murdered, warned her husband, and he fled Rome. This may have been a ploy on the part of Cesare and Lucrezia to drive her husband away. Lucrezia was delighted to be relieved of her boring husband, and Alexander and Cesare even more delighted with the prospect of arranging another profitable marriage for Lucrezia. Of course, they first had to get rid of Giovanni Sforza. Alexander asked Giovanni's uncle, Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, to get his nephew to agree to a divorce. Giovanni refused, and turned to others in his powerful Milanese family. They, however, were reluctant to quarrel with the Pope, and knowingly suggested the defense of Giovanni's proving his manhood by sleeping with Lucrezia while observed by members of the Borgia and Sforza families. Giovanni rejected the proposal--as his relatives knew he would--and accused Lucrezia of incest with her father and her brothers, Cesare and Giovanni, the Second Duke of Gandia. The Pope used the only valid argument for annulment, the non-consummation of the marriage, and he offered his son-in-law all of his daughter's dowry. The head of the Sforza family threatened to withdraw his protection if his nephew refused the Pope's offer. Giovanni Sforza had no choice, and signed a confession of impotence and the documents of annulment before witnesses. Affair with Perotto Calderon

Cesare, discovering his sister's pregnancy, was furious. He made a run at the young Perotto with drawn sword, stabbing him as he knelt before the papal throne. Perotto survived the attack, but was thrown into prison. Some days later, Perotto's body was fished out of the Tiber River, along with that of Lucrezia's chambermaid, who, it was believed, had facilitated the affair. Infans Romanus & Rumors of Incest

This subterfuge to legitimize the infans Romanus simply led people to assume that the boy was the child of Lucrezia and Alexander, or of Lucrezia and Cesare. The historian Potigliotti suggests that Lucrezia insisted on the two papal bulls because she didn't know which of her two lovers, her father or her brother, had actually fathered the infans Romanus. Giovanni was passed from guardian to guardian, eventually ending up with Lucrezia in Ferrara as "her half brother." The unfortunate Giovanni never inherited his titles, and, after a lifetime of serving as a minor functionary in the courts of the Vatican and France, died relatively unknown in 1548. The rumor of incest as his origin that began with Lucrezia's first husband's attack on his former in-laws has persisted to this day. When it was rumored that the undisclosed woman who gave birth to the child was Lucrezia, the rumors of incest began to expand and multiply until at length they reached the historians Francesco Guicciardini and Niccolo Machiavelli, who recorded them for all time as a well-established fact. It may be true, or it may be that he was the offspring of Lucrezia's indiscretion with Perotto. Second Marriage: Alfonso of Aragon

As was so often the case at that period of history, political allegiances began to reform, to change, so that ally became adversary. Alfonso suddenly found himself and his family out of favor, as Alexander turned his support to the enemies of Naples. While the Pope assured his son-in-law that he was still in favor--even giving the young couple a castle, along with the city and lands of Nepi--Alfonso knew that all was not well. Alexander had given the governorship of Spoleto and Foligno, an office usually reserved for cardinals, to Lucrezia, essentially rendering Alfonso as a non-functioning consort. Lucrezia, although only nineteen, was not a mere figurehead, and administered the city well. After a few months, the Pope persuaded his daughter and her husband to return to Rome, to await the birth of the couple's first child, who would be named after her father, Rodrigo. Not long after, Alfonso was set upon by a group of armed men. He was seriously wounded and left for dead, but brought into the Vatican apartments to be attended by his distraught wife. Lucrezia stayed by her husband's bedside, fully realizing that her brother, Cesare, was behind the attack. Alfonso almost recovered. Unfortunately, he was visited by his brother-in-law, who ordered Lucrezia, his sister-in-law, and the servants out of the room. According to accounts, Cesare ordered his principal henchman to strangle Alfonso. Alexander, seeing his daughter and daughter-in-law fleeing the bedroom in terror, sent his chamberlains to try to prevent the murder. By the time they arrived, it was too late. As Burchard reported, "Since Don Alfonso refused to die of his wounds, he was strangled in his bed." Lucrezia as Administrator of the Vatican & Church

A year later, while surveying his new acquisitions resulting from the defeat of Alfonso's father, Federigo, King of Naples, Alexander left the administration of the Vatican and the Church in the hands of Lucrezia. A woman of twenty-one, acting as the head of Christendom, did not shock the cardinals of the Curia, accustomed as they were to the excesses of the papacy of Alexander. The Pope was busy amassing money to finance the military adventures of Cesare, and to obtain a grand dowry for Lucrezia, whom he hoped to marry off to a third husband, this time, if possible, to royalty. Third Marriage: Alfonso, Duke of Ferrara

Afonso d'Este was a strong silent type, interested in artillery, music and brothels, and was soon captivated by his new wife. Lucrezia had four children and became a loving wife and admired mother--except for her romance with the poet Pietro Bembo, which ended in 1505. Curiously, her relationship with Bembo conferred upon her an artistic sensibility that increased her reputation in Ferrara. Patroness of the Arts, Devoted Wife & Mother

Lucrezia’s Death

Lucrezia was mourned by everyone who knew her. It was not until later, when historians began to rewrite the Borgia story for their own purposes, that she was quite possibly misunderstood and hence the legend of “Lucrezia the Infamous” was born. So Lucrezia Borgia, accused of participating in the murders carried out by her father and brother, accused of incest with either her father or brother (or both), died a pious and respected consort of the Duke of Ferrara. One of her sons, Ercole, succeeded his father as Duke, and another, Ippolito, became a cardinal. Both were known for their love of luxury, and, as such, carried on the Borgia tradition of material excess. The Poison Murders

Shortly after the eleventh anniversary of his accession to the papacy in August 1503, Alexander fell ill. So did Cesare, and around this coincidence a rumor grew in Rome that some authorities, such as McBrien, believe to be true. Alexander and Cesare had dined with Cardinal Adrian Corneto at the latter's villa. It long had been believed that the Borgias had intended to make Corneto their next victim. Indeed, Corneto thought that he had been poisoned, but had saved himself by switching the cup that Cesare had prepared for him. The unsuspecting Alexander and Cesare both drank freely from it. Within a few days, Cesare recovered, but his father lingered for a few more days and died at the age of seventy-seven. Whether it was through callousness or timidity that Lucrezia was an observer and supporter of the crimes of her father and brother, there is no specific evidence to suggest that she objected her family's use of murder as a solution to their political problems. Until becoming the Duchess of Ferrara, she certainly was a sexually active young woman, and may have indeed committed incest with members of her family. Perhaps she changed as she got older, or perhaps she became more discrete. Yet, she was no worse than many other ladies of her time, and by the standards of the rest of her family she was positively well behaved. Regardless, there seems to be little basis for her reputation as the historical archetype of murderer by poison, the sort of Renaissance “black widow” that we have come to believe she was.

Text generously stolen from the following references:

|